What do the New Acres of Texas Grapes Hold in Store for Wine Consumers?

In my previous blog post (Texas Wines Heading South? What Texans Can Learn From The Texas Grape Production and Variety Survey), I showed that Texas wine were heading south: heading for the southern reaches of Europe for grape varieties that love our warm (hot) but changeable Texas climate. This was based on an analysis of the changes in producing acres of grapes in Texas from 2005 thru 2010.

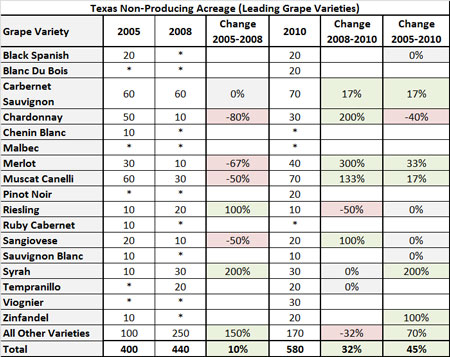

The table shown above is another analysis, but this time of the acres of wine grapes not yet into production (non-producing). This, in fact, should be another (and possibly better) view of the direction of the industry as determined by what the Texas winegrowers are planting. In most cases, the determination of what grape varieties to plant is (or should be) based on discussions between the growers and representatives from Texas wineries who have (or should have) a good indication of the wines their customers want to buy. I sincerely hope that wineries aren’t still making Merlot simply because the winery owner likes Merlot.

Well, here goes…

- Cabernet Sauvignon is still being planted in Texas as is Merlot. This is likely for two reasons: the first is that Cab and Merlot sell, both individually and when blended together (The Bordeaux Model). Secondly, as both Kim McPherson and Les Constable among many tell me, Cabernet and Merlot can be blended with other (and lesser known and warmer weather) grape varieties like Sangiovese, Tempranillo and even Tannat to make blended wines with real Texas character (and that sell). If you look around warm places like the Rhone Valley, Spain and even Australia, good marriages are often made in the blending tank.

- Chardonnay in Texas may be finally left behind. It showed a net decrease of 40% from 2005 to 2010 despite losses shown in 2008 and gains in 2010. This could also indicate that Chardonnay has problems in Texas (weather, disease, etc.) and needs to be replanted in order to stay around these parts.

- Texas Muscat Canelli is still gaining in acceptance. It is an extremely versatile grape that can be made in to wines that are dry, off-dry, sweet and sparkling. Muscat always adds something to the pot when it is blended to a variety of other white grapes. In this regard, some call it “Texas magic”. It’s only potential issue is it’s tendency to bud out early making it susceptible to an acknowledged Texas nemesis: late spring freezes.

- Winemakers must have seen a market of Texas-grown Syrah. However, the gains in planting it showed from 2005 to 2008 were not matched between 2008 to 2010.

- Zinfandel is up in these stats just like it was in producing acres. Why? I’m not sure, but would love to hear from growers, winemakers or consumers on their Texas red Zin experiences. Alternatively, is this growth being lead by its use in Texas blush wines?

- Interestingly, the big growth in “all other varieties” in the 2005 thru 2008 period (150% increase) showed and loss of 32% in 2008-2010 for a net increase of 70%. What is that all about? Perhaps, it shows some hesitation on the part of growers. Why? Perhaps it’s because of resistance from the distributors to handle wines made from what they consider “no-name” varieties, or maybe it is just the time it takes to see results.

One possibility that I barely mentioned above is that some of the variability in these data may be due to the difficulties of Texas grape growing and the fact that we are still sorting out important issues here (growing conditions, seasonal weather extremes, climate, drought, disease, soils, and the lists goes one).

While we all (growers, winemakers and consumers) would like decisions to be made quickly as to what will be our keystone grape varieties and move on, the fundemental fact remains that definition of a region’s defining grape varieties is a slow process that in many of the regions of Europe took a thousand years to sort out. In the new wine world, even with the help of modern technology, it still took a hundred years in places like California, Australia and South America.

As Texans, we like to think that just because we think we can do it…we can, and that it should happen quickly. But, we are not adverse to hard work. The long history of Texas agricultural success has been one based on the grit and determination of its rural people.

As you can see, these numbers and my comments perhaps prompt more questions than they give answers to where Texas is going. But, let me remind you that these are the uncertain but exciting times in the Texas experience. It is something akin to what was happening in California’s Napa and Sonoma regions back in the 1960s and 70s. As a long time Napa winery owner reminded me back in 2008, they didn’t know where it was all going back then either in the 60s.

Please remember to eat local and don’t forget to drink local, too. It will support the process of change and the betterment of Texas wines. It’s time to saddle up and experience Texas wines. Visit some wineries and taste some good wine and possibly some bad wine, too. But, taste and learn while looking for the best of Texas wines and especially those that bring true value to the local wine experience.

Zinfandel is one of the hardest vineyards to manage in Texas for several reasons. Zinfandel has the ability to put on huge crops, 2lb clusters and very tight berries. For these reasons a bold red is hit or miss, and a chess game to get to harvest. Black rot, grey rot and every other fungal disease can run wild in zinfandel if not controlled and managed from bud break. It is possible to lose an entire crop if fungal diseases are not managed and checked daily in the weeks leading up to harvest. In my experiences with Zinfandel a bold red cannot be made every year. In some years with big crops and a wet august it is almost impossible to get the color and brix to the point to make a quality red, and a blush is the best it can do.