Mysterious Alchemy – The Aging of Wine

Three Part Guest Blog by Michael Vilim

Michael Vilim is an Austin-based restaurateur with two first-class restaurants: Mirabelle and Castle Hill Cafe. He also serves on the Board of Directors for The Wine and Food Foundation of Texas, a charitable organization that supports scholarships for deserving culinary students and grants for deserving educational projects. http://www.winefoodfoundation.org/

Part 1 – To Age or Not to Age? That is the Question

A too frequent scenario: dinner party at a friend of a friend and I am introduced as a wine expert. The host promptly disappears (one hears rutting through a closet in another room) and returns with a very old bottle of wine and a face simultaneously revealing grave concern sparked with a glimmer of hope. The question is posed, “When should I drink it?” “Tonight, of course!” Very sound advice rarely heeded, but secretly I am usually thinking, “Oh, about 10 years ago….”

All wines benefit from short-term aging. Freshly made wines are raw, tannic and suffer from various steps of the winemaking and require time to round out into balance. When bottles of wine travel distances, they require a few weeks of rest for the wine’s chemistry to settle down and show well.

But something glorious happens to wines capable of aging for the longer term. I have witnessed bottles of raw, gritty, undrinkable juice abandoned in the corner of a cellar only to be rediscovered years later, now soft on the lips, wildly aromatic and with a flavor and bouquet unlike anything else I’d ever consumed. That experience is the “Grail-like” pursuit of aging wine and the chemical transformation that occurs inside the bottle is a very mysterious alchemy indeed.

But something glorious happens to wines capable of aging for the longer term. I have witnessed bottles of raw, gritty, undrinkable juice abandoned in the corner of a cellar only to be rediscovered years later, now soft on the lips, wildly aromatic and with a flavor and bouquet unlike anything else I’d ever consumed. That experience is the “Grail-like” pursuit of aging wine and the chemical transformation that occurs inside the bottle is a very mysterious alchemy indeed.

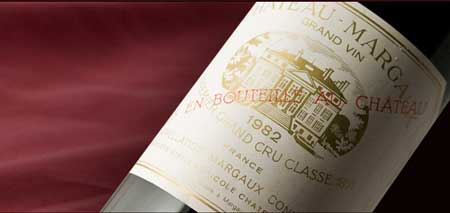

A Margaux for Christmas Dinner?

One doesn’t have to be an expert to appreciate the bouquet of aged fine wine. I once took a few bottles of 1979 Chateau Margaux home for Christmas dinner. My sisters, quite vocal in their preference for white wine, on tasting the Margaux exclaimed in unison and almost in rapture, “Well, this isn’t so bad.” Sure, not so bad at $300 a bottle, such that even my sisters could recognize the overwhelming greatness before them. But, if they had drunk the same Margaux on its release, they would have hated it despite its price tag.

I am of the generation of wine drinkers that grew up with mature wines still available in wine shops. California wines were just beginning to become popular. The luscious, fruit forward Australian wines were yet to be imported. At this time, a young wine drinker learned about wines like an apprentice, talking with wine shop owners and tasting wines from the cellars of generous collectors with mature palates. The popular wine review industry was in its infancy. Ten year old bottlings of decent Bordeaux, Burgundy, Rhone, Chianti and Rioja were abundant. They were a bit hit-or-miss depending on storage and shipping conditions, but they had softened and grown fuller and would now reveal bottle bouquet – the complex odors a good, mature wine develops with bottle age, and is probably fine wine’s greatest charm. This is my preference in a bottle of wine. Somewhere in the early nineties, all that wine was snapped up as a result of good economic times and wine’s growing popularity.

I am of the generation of wine drinkers that grew up with mature wines still available in wine shops. California wines were just beginning to become popular. The luscious, fruit forward Australian wines were yet to be imported. At this time, a young wine drinker learned about wines like an apprentice, talking with wine shop owners and tasting wines from the cellars of generous collectors with mature palates. The popular wine review industry was in its infancy. Ten year old bottlings of decent Bordeaux, Burgundy, Rhone, Chianti and Rioja were abundant. They were a bit hit-or-miss depending on storage and shipping conditions, but they had softened and grown fuller and would now reveal bottle bouquet – the complex odors a good, mature wine develops with bottle age, and is probably fine wine’s greatest charm. This is my preference in a bottle of wine. Somewhere in the early nineties, all that wine was snapped up as a result of good economic times and wine’s growing popularity.

Wines Today – What does this mean for aging?

Wine is made differently today than 20 years ago, and the difference is critical in how it is enjoyed and aged. Today, wine is much more of a commodity and the search for markets and market-share has exceeded the pursuit of like-minded connoisseurs around the world.

The goal of today’s highly sophisticated winemaking is to make wine that in many ways approximate mature wine, but ironically, probably won’t mature well. Why? Because the elements that enable wine to improve with age and develop bottle bouquet inhibit the enjoyment of the fruit in a recently released wine.

To increase the fruit in a young wine and tame its tartness, vines are left to ripen longer and longer on the vine, the sweetness of the fruit increases, the acids in a wine are reduced, meaning less tartness and a softer, rounder feel. But acidity is critical as one of the preservatives for long-lived wines. Good acidity stabilizes the chemical balance in, it enhances the production of sweet smelling compounds called “esters,” and it increases color hues and provides a fresher taste. Also, mature bottle bouquet is a result of the interaction between a wine’s alcohols and acid.

The wine being produced today is undoubtedly better than at any time in history. However, the case could be made that there isn’t really that much more great, age worthy wine, it’s just that jug wine got really, really good. These “New World” styled wines possess lots of appeal, which is best realized with the benefit of short-term aging, such as three months to two years. With additional time, more age worthy wines will develop secondary flavor nuances and aromatics such as earth, mushrooms, spice and even the structural elements of acid, tannins and its woodiness.

The wine being produced today is undoubtedly better than at any time in history. However, the case could be made that there isn’t really that much more great, age worthy wine, it’s just that jug wine got really, really good. These “New World” styled wines possess lots of appeal, which is best realized with the benefit of short-term aging, such as three months to two years. With additional time, more age worthy wines will develop secondary flavor nuances and aromatics such as earth, mushrooms, spice and even the structural elements of acid, tannins and its woodiness.

Since fruit is such a large part of the modern wine palate, the majority of newer wine drinkers move on. But some very experienced wine lovers, especially wine professionals, find this latter stage to be quite attractive, precisely because the emergence of more complexity in wine’s aromas and palate. This “window of drinkability” can last for a year or two before the fruit disappears all together. A decision must be made to either be drink up or to lay the wine down for an additional 3-5 years of aging.

Stay tuned….Tomorrow will we have Part 2 of Michael Vilim’s Guest Blog Post:

What Wines to Age and How

Be the first to comment