Mysterious Alchemy – The Aging of Wine

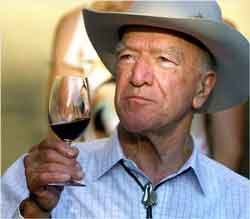

Three Part Guest Blog by Michael Vilim

Michael Vilim is an Austin-based restaurateur with two first-class restaurants: Mirabelle and Castle Hill Cafe. He also serves on the Board of Directors for The Wine and Food Foundation of Texas, a charitable organization that supports scholarships for deserving culinary students and grants for deserving educational projects. http://www.winefoodfoundation.org/

Part 2 – What is Aging, What Wine to Age, and How

So, the stages of aging are first, the pre-release sorting out of the various parts of a wine and the first years of aging such that a particular bottling comes together in harmony and balance. Second, the fruit begins to recede, and even though the acid and tannins are softening at the same time, these elements become more a part of the flavor of the wine just because the fruitiness has blown off. The next phase is when a wine goes “dumb’, meaning the whole flavor profile of the wine is metamorphosing from a palate laden fruit entity into a complex, multi-layered phenomenon.

Nearly all great wines evolve through this dumb phase, when the fruit and nose are completely void, and only the structural anti-oxidant elements such as acid, tannin, and minerals are apparent, simply because their devolution is continuous and linear. They can be gritty and tart and one can hardly imagine that anything resembling good wine will ever emerge from what is inside that bottle. It usually takes 2-4 years for this stage to pass.

Wines beginning to exit the dumb stage will begin to show a nose, or bouquet, while the palate still is lacking, or “closed.” For an old world wine like a good Bordeaux or Burgundy, Italian Brunello di Montalcino, I would give 2 or 3 more years in the cellar before I opened another bottle. A New World Cabernet probably 2 years, while Oregon and California Pinot Noirs, age worthy Zinfandels (like those from Dry Creek Valley) another year of aging. There is a much trial and error in this process, and tasting a wine to determine its progress is critical.

Wines beginning to exit the dumb stage will begin to show a nose, or bouquet, while the palate still is lacking, or “closed.” For an old world wine like a good Bordeaux or Burgundy, Italian Brunello di Montalcino, I would give 2 or 3 more years in the cellar before I opened another bottle. A New World Cabernet probably 2 years, while Oregon and California Pinot Noirs, age worthy Zinfandels (like those from Dry Creek Valley) another year of aging. There is a much trial and error in this process, and tasting a wine to determine its progress is critical.

Wine’s final stage – of maturity – deserves and requires all the patience afforded because it is great wines’ highest expression. A glorious bouquet emanates from the glass such that your appreciation might begin at arm’s length, and the palate is delicate and rich at the same time, and all the components have melded together, seamless and complex. Age-worthy whites will have deepened in color and the bright, plumy reds will have lightened. Fruitiness will have given way to florals such as lilac and rose petal, spice hints such as black pepper, cardamom, star-anise or cinnamon, and earth tones of mushrooms, wet leaves and cedar. The palate is soft and sensual and resonates with the same flavors, flavors which seem to go on and on, the building blocks of acid and tannins fully integrated now and providing an invisible support for the fruit and bouquet.

Conditions for Cellaring

Cellar-like conditions are essential to the aging of wine. Aging wine in the long term is about the development of both bottle bouquet and preserving a wine’s fruit freshness. In cooler parts of the world, aging wine can be as simple as sticking bottles in a cool corner of your basement or garage and forgetting about them with benign neglect. Wine is living thing, but then so are we, and the conditions in which we are comfortable, most wines can survive as well. It is the extremes that must be avoided. A constant temperature below 65 degrees is really a minimum, because warmer levels cause a wine to develop much more rapidly and unpredictably so. A spike of heat in the excess of 85 will expand the liquid in the bottle and can dislodge the cork’s seal such that the wine will begin oxidation. Such wines never really recover their age worthiness, but can be enjoyed for a short while, maybe for a few years but cannot age much past that. With time, a nutty, sherry-like nose and palate will appear in chardonnay, for example, a condition called “maderization” or premature aging. Ongoing severe heat will spoil or “cook’ a wine, such that it becomes quite disagreeable, and smells and tastes like badly stewed fruit and vegetables.

Some humidity is required for aging wine, but with the bottles on their side the wine inside will usually keep the cork moist. It is the airtight refrigerators that remove all moisture from the air that are problematic for extended storing. Excessive light can harm wines, especially whites, and storage should also be odor-free, since molecules will permeate the cork resulting in off aromas and flavors. But as small cellar units are much more reasonable today and cellar information widely distributed, even those living in very hot climates can age wine reliably and economically. The good news is once a wine reaches maturity, a well-cellared bottle can plateau at or near its peak for several years even decades, during which changes occur quite slowly and subsequent deterioration is very gradual.

What to Age?

How do you know what wines to choose for long-term aging? A wine must be above all well balanced, with healthy, mature fruit and with the building blocks of acid (measured in a winery as pH, a wine’s total acid and mineral impact) and tannins. If your goals lean toward long-term aging, the varietals are mostly the same ones we commonly know, but the vineyards that produce long lived wines are more a result of nature and limit the amount of age-worthy wine the world will ever produce such as: Cabernet Sauvignon (and limited Merlots and Cabernet Francs) in Bordeaux, California and Washington State; Pinot Noir in Burgundy, Oregon and California, Syrah, Mourvedre and Grenache in the Rhone, Australia and Spain; Nebbiolo, Sangiovese, and Aglianico in Italy; Tempranillo in Spain, and a few whites: Riesling in Germany; Riesling, Gewurztraminer and Pinot Gris in Alsace; Chardonnay in Burgundy and California; and perhaps Viognier in Rhone and Semillon/Sauvignon Blancs blends in Sauternes.

How do you know what wines to choose for long-term aging? A wine must be above all well balanced, with healthy, mature fruit and with the building blocks of acid (measured in a winery as pH, a wine’s total acid and mineral impact) and tannins. If your goals lean toward long-term aging, the varietals are mostly the same ones we commonly know, but the vineyards that produce long lived wines are more a result of nature and limit the amount of age-worthy wine the world will ever produce such as: Cabernet Sauvignon (and limited Merlots and Cabernet Francs) in Bordeaux, California and Washington State; Pinot Noir in Burgundy, Oregon and California, Syrah, Mourvedre and Grenache in the Rhone, Australia and Spain; Nebbiolo, Sangiovese, and Aglianico in Italy; Tempranillo in Spain, and a few whites: Riesling in Germany; Riesling, Gewurztraminer and Pinot Gris in Alsace; Chardonnay in Burgundy and California; and perhaps Viognier in Rhone and Semillon/Sauvignon Blancs blends in Sauternes.

The traditional choices from Europe are still the best, because they are wines that have good track records of aging well. The New World styled big fruit wines have yet to demonstrate whether they will be ageworthy or not, so one should stick to the classically made California reds of which a few of the excellent choices are Chateau Montelena, Ridge “Monte Bello”, Joseph Phelps Insignia, and Dominus.

Wine collections are very much like an individual’s library of books and music. Collections grow haphazardly with enthusiasms and opportunities, and can be a snapshot of a time and place in your life. Every time you reach for a bottle from a cellar, a memory is invariably pulled along with it. And the pleasure of buying fine wine, aging it to maturity, and then sharing delicious mature wine of great value with your family and friends is quite a rewarding feeling. Of course, one should have started collecting wine about the same time as your personal financial plan—right out of college, but the next best time is today. And once you get into the ebb and flow of aging wine, it can be the most reliable and economical way to ensure a steady supply of great wine that is ready to drink.

Stay tuned….Tomorrow will we have Part 3 of this Guest Blog Post:

Texas Wine Selections and Aging – Comments and experiences from Michael Vilim, Jane Nickles (Texas Culinary Academy) and Russ Kane (VintageTexas.com).

Be the first to comment