Quote from the headline in The Comanche Chief Newspaper of July 4, 1913…

While most of the nation had to wait until 1919 to enjoy the “benefits” of alcohol prohibition, in 1913 many in Texas got to feel it upfront and early. July 1st of that year was when the so-called Allison bill, a new Texas law, went into effect. Under the terms of the legislation, no “wet goods”, including wine, could be shipped to a “dry” territory of Texas. Even in a “wet region”, they had to be shipped to a licensed liquor dealer or else a pastor or priest. Furthermore, the pastor or priest if wanting to receive wine had to prove that the wine was going to be used for sacramental purposes and not merely, as was said, ‘for the sake of the stomach’. This was the most rigid liquor prohibition law that was passed in Texas that put a near-permanent end to the Texas wine industry.

In 1919, a temporary national wartime prohibition and several regional prohibitions were replaced by the Volstead Act, the popular name for the National Prohibition Act in the United States. The act established the legal definition of intoxicating liquors as well as penalties for producing and selling them. Although the Volstead Act prohibited the sale of alcohol, the federal government found it hard to enforce.

In 1921, The Austin American Newspaper reported Ed Moellar, the city marshal of New Braunfels, and three others were arrested when officers seized 250 gallons of alleged illegal mustang wine and a liquor still. The raid, confiscation, and arrests were made by Frank Hamer of Austin under order from the U.S. federal prohibition enforcement officer. Information of the alleged violations of the law came to the ears of the authorities from private sources aided by preparations before the enforcers advanced.

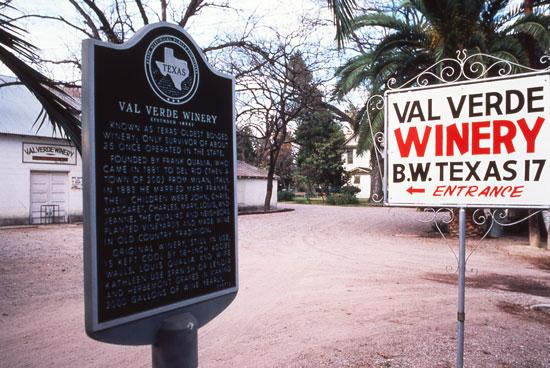

During prohibition, the only Texas winery that remained in commercial operation was the Val Verde Winery owned by the Qualia family in Del Rio. It was originally started in 1883 by Franchesco Quaglia (the family later changed the spelling of their name to ‘Qualia’). The winery remained open during prohibition by making and selling legal sacramental and medicinal wines, by selling grapes to home winemakers around the state that made wine for their personal or family consumption, plus by farming and cattle ranching.

In 1933, the Cullen–Harrison Act, legalized beer and wine sales of low alcohol content, and in the same year Prohibition laws in the U.S. were repealed. Upon repeal of national prohibition, 18 states continued prohibition in various forms at the state level. In 1935 Texas voters ratified a repeal of the state dry law. Thereafter, the prohibition question reverted to the local local-option statutes. The last state, Mississippi, finally ended prohibition in 1966. Almost two-thirds of all states adopted some form of local option which enabled residents in political subdivisions to vote for or against local prohibition. Therefore, despite the repeal of prohibition at the national level in 1933, 38% of the nation’s population still lived in areas with state or local prohibition.

By 1937, Texas wineries were again being started. The list below was assembled using the records of bonded U.S wineries at Cornell University. In some years the records are spotty or outright missing. Shown below are the name, the permit number, year of permitting and location for the first ten post-prohibition Texas wine bonding permits (where data could be found):

- Sadorene Winery, Permit #1, 1937 (San Antonio)

- Southern Winery, Permit #2, 1937 (San Antonio)

- Zavala Winery, Permit #3, 1937 (Crystal City)

- Bonita Vineyards, Permit #4, 1937 (San Antonio)

- Texas Winery, Permit #5, 1937 (Fredericksburg)

- Permit #6 – missing

- Niederauer Winery, Permit #7 (Brenham)

- Caltexas Wines, Permit #8 (Houston)

- Permit #9 – missing

- Sant Lucia Wines, Permit #10 (Houston)

It is interesting to note that Val Verde Winery (started in 1883) is not included in the early post-prohibition Texas winery bonding permits. It has Texas winery permit number 17. By the time the long-since opened Val Verde Winery reached the point of getting their post-prohibition permitting sorted out, they had to settle for the seventeenth bonded wine license in the State of Texas.

After the repeal of Prohibition, twelve Texas businesses were licensed in the first several years after the repeal of prohibition. Early post-Prohibition hill country wineries were Sadorene Winery, Southern Winery and Bonita Winery in San Antonio with Niederauer Winery in Brenham. Since much of Texas was dry for sales of alcohol and the state government in Austin was hardly supportive, it was difficult to start and run wineries as evidenced by their decreasing numbers from 1940 through to the 1950s and early 1970s.

One name that is often lost in history is that of Ludwig Vorhauer, a horticulturist and immigrant from Austria who settled northwest of Fredericksburg in 1913. He grew nut and fruit trees, then opened a nursery and a large 25-acre vineyard. In 1937, after a long wait during prohibition, the Vorauer family’s Texas Winery received Texas winery license number 5. While Ludwig died only a year after starting the winery, his wife and sons ran their winery until 1955 (the same year that Niederauer Winery, with permit number 7, also closed). At this point, Val Verde again became the only operating winery in Texas.

Other than the very short-lived Lindsay-Brania Citrus Winery (1938), there was not another commercial Texas winery bonded until 1973 when the Rio Grande Valley Citrus Winery was bonded. Following this event, starting in 1977 came the founding of several new Texas wineries of the modern period with Guadalupe Valley Winery (1977), Llano Estacado Winery (1978), La Buena Vida Vineyards (1979), and Fall Creek Vineyards (1980). The records for 1981 were missing, but in 1982, five wineries were licensed: Chateau Montgolfier Vineyards, Cypress Valley Winery, Davis Mountain Winery, Sanchez Creek Vineyards, and Moyer Texas Champagne Company. The following year (1983) brought the licensing of La Buena Vida (Lakeside), Oberhellmann Vineyards (later named Bell Mountain Vineyards), Pheasant Ridge Winery, Messina Hof Winery, and Wimberly Valley Wines.

Admittedly, the data has holes in it and the format and information recorded changed over this period making it difficult to know what was going on at the time. If you know of other sources of information, or can come up with a better list… Go for it! But, let me know what you find and I will be glad to highlight it via social media and my VintageTexas blog.

Be the first to comment