In Texas Native Grapes: Know Them, Grow Them… Cherish Their Worldwide Legacy – Part 1 (click here), we reviewed what are native grapevines, how they can benefit wildlife with cover and sustenance and humans providing grapes, jellies and jams, and wine. We also discussed how to identify some of the more common Texas native grape varieties in the wild. Now, we are moving on to the roles of Texas native grapevines in history up to modern day, and finishing with how to grow them.

European Emigrants to Texas were Farmers and Winemakers

Most European emigrant farmers that came to Texas in the 1800s, brought a love of wine. It’s a matter of fact that Stephen F. Austin sent pamphlets to European countries to encourage people to come to Texas, a land that he said was destine to provide grapes and wine for all the United States. However, the vinestock that they brought to Texas did not grow. However, many found an alternative – wild-growing Mustang grapes also called the “Cutthroat Grape” because of its harsh acidic characteristic.

However, farmers crushed and fermented mustang grapes and added lots of sugar to counter the bitter acidic taste. Click here for Mustang wine recipe. They also used Mustang grapes to make a Springtime pioneer favorite – Green Grape Pie (click here for the recipe). Mustang wine became a mainstay of farm families throughout Texas. Farm records from the 1800s show that many farms had an inventory of at least one or two barrels of Mustang wine.

Phylloxera Hits European Vineyards but Not In the USA

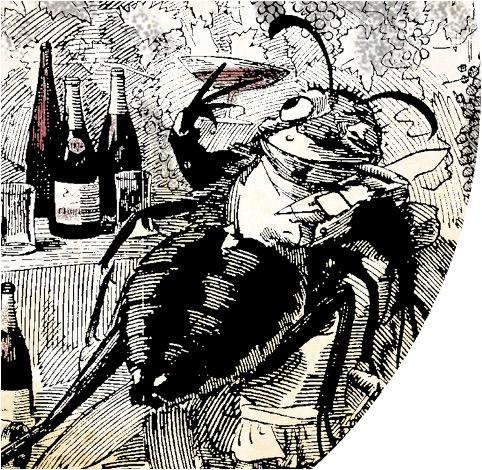

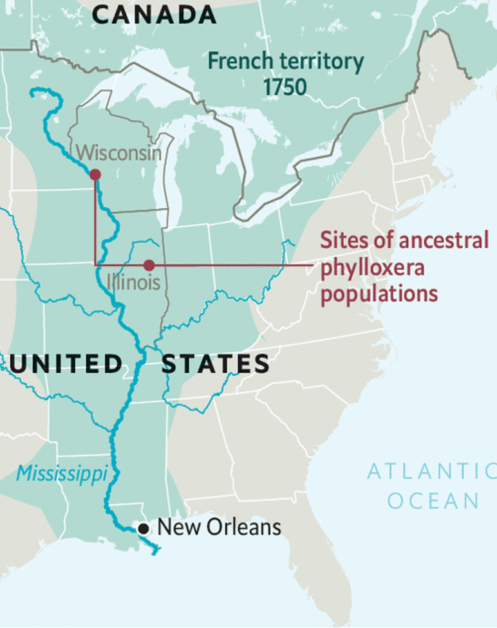

Phylloxera vastatrix or “Devastator of Vines” – also known as Daktulosphaira vitifoliae, is an insect pest (in one stage a root louse) that attacked the root of European Vitis vinifera grapevines. Phylloxera was originally native to North America but it spread to Europe in the 1800s with imported American plants and vinestock.

Many native American grapes are resistant to Phylloxera, but European vinifera wine grapes don’t have the counter measures of the American native grape varieties. This deficiency makes the roots of vinifera grapes very susceptible to attack by Phylloxera. After more than a decade, Phylloxera resulted in the worst European agricultural disaster with loss of 70% of the vineyards in France alone.

A little known fact is that Phylloxera originated from the region around the Mississippi River Valley in America and spread east of the Rocky Mountains. Over thousands of years, many native American vines developed physical and chemical protections for roots. European vinifera did not evolve with Phylloxera and do not have this protection. American natives are susceptible to less-critical Phylloxera foliar damage but not to fatal root damage.

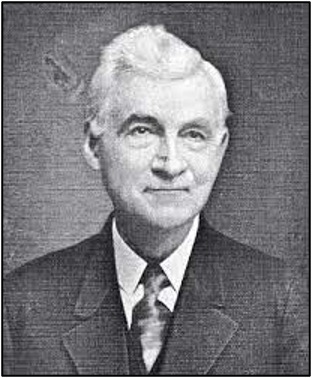

Enter Thomas Volney Munson

Thomas Volney Munson (often referred to as T.V.) attended Kentucky A&M and eventually moved to Denison, Texas in 1873 where he started a horticulture business. In addition to being a scientist and an astute business man, Munson organized the Texas Horticultural Society. By 1886, his work on grape hybridization and native grape classification gained Munson international fame.

Munson communicated with many researchers and scientist in Europe who were trying find a solution to the Phylloxera crisis. In 1886, he sold Texas vinestock for research at a new institute in Montpellier, France. Munson corresponded with Pierre Viala at the Montpellier Institute about Phylloxera, then hosted Viala’s French delegation to the U.S. at his home in Denison. Viala, who headed the delegation, planned to spend two days with Munson and ended up staying with him for two weeks for discussions and nearby field work.

Viala and Munson discussed that the French had already tried American native vines from other states for rootstock in their vineyards but they all failed. Finally, since the French soils and those in central Texas were similar (calcareous soils with high pH), Munson advised that his first choice for rootstock for France was Vitis berlandieri, a Texas native growing in this area and arranged to send cuttings.

Viala 1888 Report in France

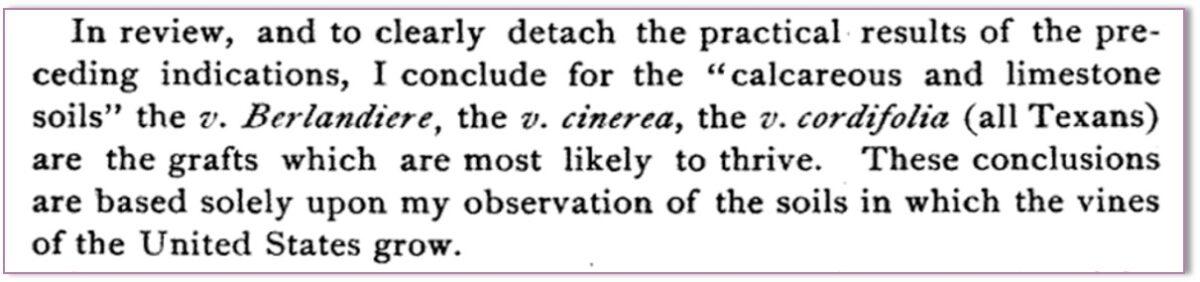

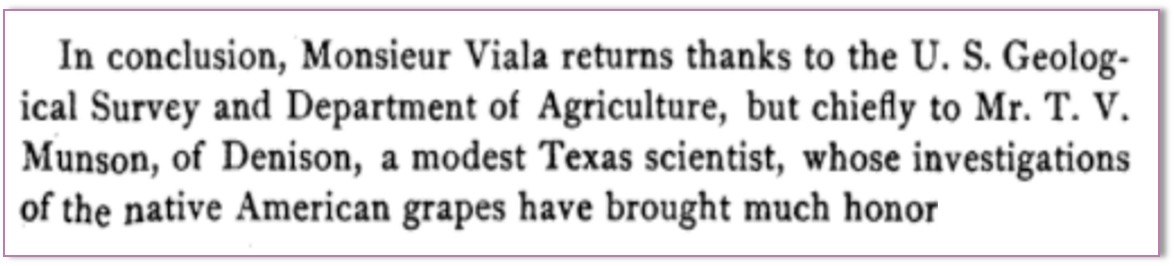

Viala’s report summarized the findings of his delegation’s trip the U.S. and highlighted the native grapevines that Munson recommended – Vitis Berlandieri, Cinerea, and Cordifolia (all Texans) due to the similar nature of the soils in France and Texas (see below).

Viala also acknowledged the helpful insights and recommendations that Munson provided:

For his contribution in the battle against Phylloxera in France, Munson received The Chevaliers du Merit Agricole in the French Government Legion of Honor. The announcement of this honor was made December 1888, and word arrived in Denison with the headline on January 9th… “Texan Leads the World”.

Munson Epilogue #1 – Rootstocks Worldwide

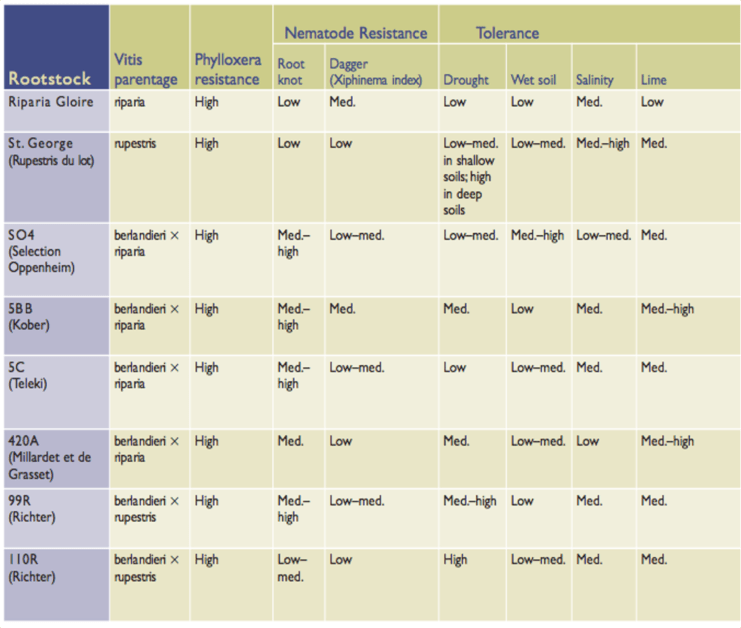

Munson’s vines proved compatible for French soil. They were difficult to graft but eventually hybrids of these grape varieties from Texas were found to work. Today, nearly all V. vinifera grown around the world are on rootstock designed for specific issues. Many varieties of rootstock are derived from Texas native grape varieties and their hybrids.

Munson Epilogue #2 – Native-Vinifera Hybrids Resist PD and Make Good Wine

Texas native grapes are now making European Vitis vinifera wine grapes resistant to another major vineyard disease – Pierce’s Disease (Xylella fastidiosa) spread by flying insects, but the one of greatest concern in Texas are sharpshooters. PD is common in southern states like Texas and is a growing problem in California as the boundary for PD in their vineyards moves northward with global warming into high value vineyard properties.

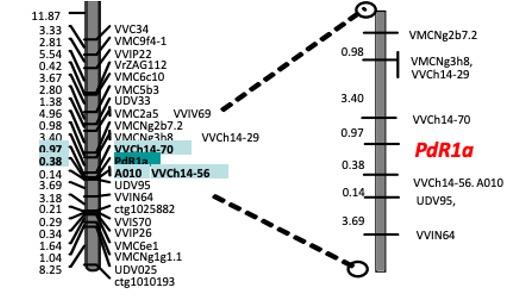

V. arizonica, a native grape variety found in Texas, New Mexico and Arizona, has a unique “single gene” resistance to PD.

It was shown that this gene can be transferred if V. Arizonica was crossed with vinifera. Dr. Andy Walker and his researchers at U.C. Davis in California inserted this gene into vinifera grapes using natural cross-breading and confirmational genetic testing, not artificial gene editing. What are now being called the “Walker Varieties” are new varieties of wine grapes with 95-97% V. vinifera and 3-5% V. arizonica. They are PD resistant and, just as importantly, make good wine. Click here for more information on Walker grape varieties.

Growing Texas Native Grapes by the Numbers

- Select a variety of native grape the grows naturally in your ecoregion. A local native in East Texas is V. rotundifolia (Muscadine). Going westward from I-45 you might find V. Mustangensis (Mustang) a more compatible grape to grow.

- Rescues can be rooted from wild “soft or semi-soft wood” cuttings, or grown from “layering” the existing vine’s canes under the soil to root.

- Remember that most natives in the wild are “dioecious,” or have separate male and female plants. So, look around to see if some of the vines have fruit while others do not.

- Purchased native vinestock are often cultivars, ~30 of Muscadine alone, many are self-fertile and do not require separate male and female plants.

- Plan to support the vines. You can use a fence, trellis, or even surrounding trees and shrubs for a more natural look.

- Importantly, be aware of soil type and habitat for the grapes you want to grow.

- Plant vines with roots, water to get the vine established, then let them go (unless in extended drought). Too much water with grow more vines but not more fruit.

- When the grapes are ripe, the call will go out and wildlife will be there, and birds will descend. So, if you want to harvest grapes and not feed wildlife, make sure you use netting as the grapes start to ripen.

- If you want to increase your yield of grapes, prune the vine to reduce the number of canes. Need a balance between fruit and leaf growth in the canopy.

- It is possible to have a “green harvest” of the grapes in late Spring to make a pioneer’s delight: Green Grape Pie (click here for recipe). This early harvest will result in fewer, but better grapes at harvest.

- Make juice, jam, or wine, or just let birds and wildlife eat the grapes.

If you are like me and living in east Texas, I recommend that you try growing Muscadine. Here are a few good cultivated varieties of Muscadines that can be purchased from nurseries or even online:

- Supreme – most popular variety with large grapes with crunchy skins

- Fry – classic Muscadine flavor and aromatics (like Concord with cotton candy nuances)

- Nesbitt – self-fertile, slow ripening and a good backyard grape, good acidity.

- Carlos (white) and Noble (red) – For eating and making juice and wine. Smaller grapes. Even ripening good for single harvest.

- Southern Home – Muscadine interspecies cross. Attractive vine with good flavors.

Here are a few more important aspects of growing Native Texas grapes:

- Plan at least six months ahead of time.

- Gather & root or purchase vine stock for Spring planting.

- Find a sunny or part shade location with good drainage,

- Get soil tested (Muscadine needs mildly acidic soil – pH 6-7 like sandy east Texas soil) that can be a problem in some places (like Houston where we mostly have gumbo clay). Mustang grapes are more tolerant of mildly acid or alkaline soils. You may also want to try native inter-species cultivars with vinifera like Blanc Du Bois or Black Spanish or a Walker variety like Camminare Noir. Click here for more information on Walker grape varieties.

- In higher pH soils, vines can become chlorotic and turn yellow that will limit the amount of fruit set and ripening. If this is a problem, you might need soil amendments or try growing a cultivar with rootstock compatible with your soil.

— — — — —

I hope that you enjoyed this rather long blog, especially when you consider both Part 1 and Part 2. Let me know your experience if you try to grow native grapevines in your garden. Cheers and have fun.

Be the first to comment