I recently had the opportunity to give a presentation at a Native Plant Society of Texas meeting that combined my interests of grapes, wine and native plants. Since it was well received by the 60-75 people in attendance and more online via Zoom, I figured it would be good to share this presentation with my VintageTexas readership, too. A link to Part 2 is also provided at the bottom of this page. Here goes…

Why are Native Grapes So Important? Think Sustenance

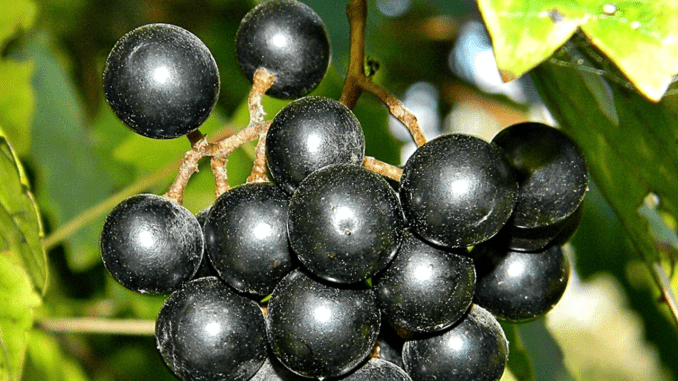

In the wild, grapes can hang on the vine between June and October, and in some cases, can remain on the vine into winter. They are moisture- and sugar-laden and an energy-rich food. Native grapes like European varieties are consumed by wildlife & humans. Their juice provides a refreshing drink and can also be fermented to make wine or used to make delectable jellies and jams. However, the taste of native grapes varies from what you might expect from European wine grapes.

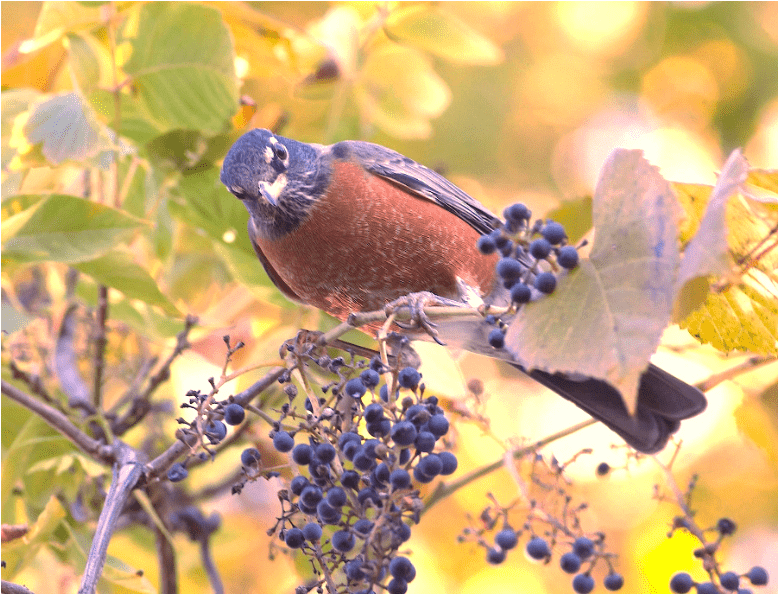

As many Texas grapegrowers already know, grapes are an important food source and attract gamebirds and many species of songbirds particularly when the fruit starts to ripen. Several mammals that consume grapes include black bear, fox, opossum, raccoon, skunk, and squirrel. Raccoons and birds seem to the bain of Texas winegrowers. Rabbit and deer browse on the foliage and stems.

Naturalistically, wild grapevines are valuable as a sources of both cover and food for wildlife. Insects are attracted to their flowers, leaves and ripe sugary grapes. Insects that feed on the foliage include: aphids, leafhoppers, beetles, midges, mites, and scale insects. These insects are a particularly good protein source for birds and their young.

What is a Grapevine?

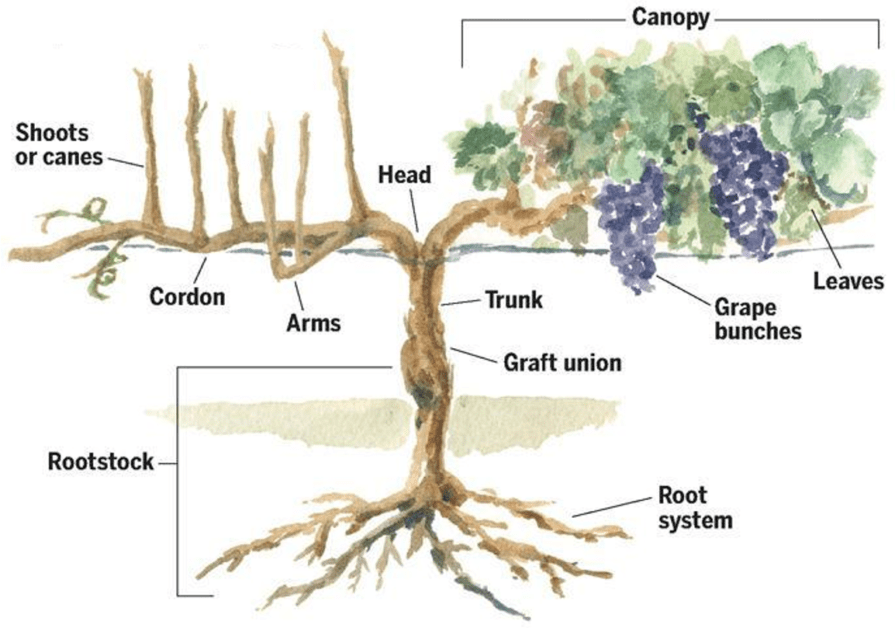

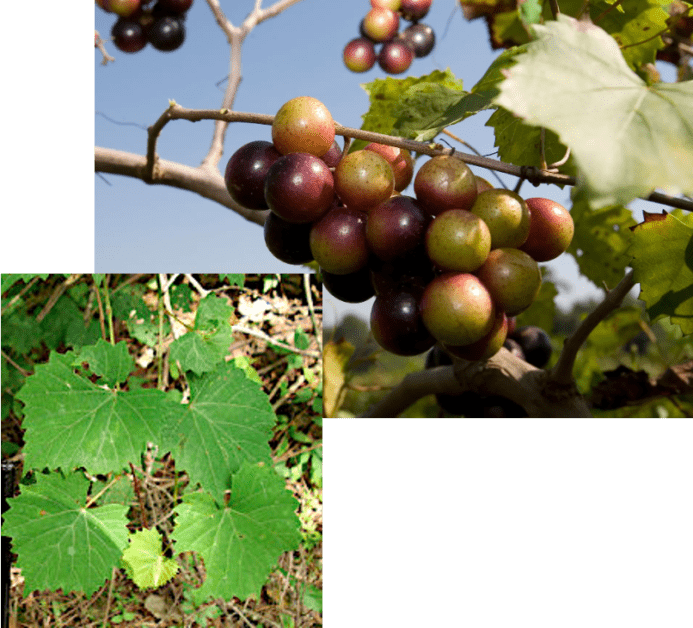

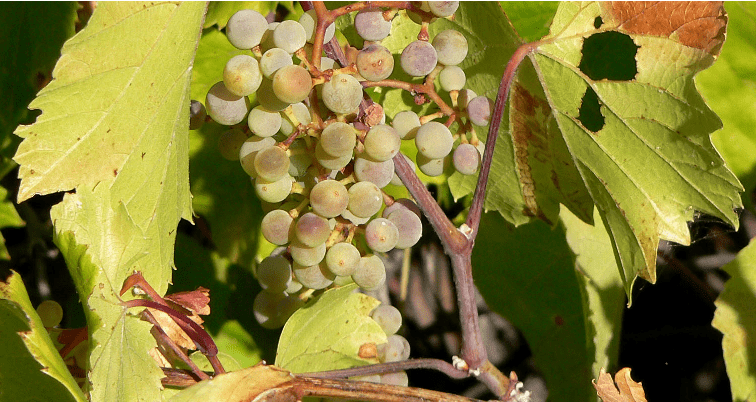

Grapevines are perennial plants in the genus Vitis. Like many native plants, they have extensive root systems that allow them to be reasonable drought tolerant. They are also climbing plants with tendrils. The vines seek sunlight encouraging them to climb and the tendrils reach out like arms and fingers to grab on to other plants, trees and structures that help them find it. The vine’s leaf canopy provides photosynthesis and mottled shade for its fruit. Grape leaves are generally cordate (heart-shaped) with lobes and are often serrated. In the wild, grapevines can grow up 50 feet or more, often supported by trees. When cultivated, they can be pruned and trained on a trellis.

How do Our Native Grapes Differ from European Vitis Vinifera Grapes?

Native American Grapes. Wild grapes generally have male and female plants. In nature, grapevines propagate by seeds distributed by wildlife that can promote natural changes, but they can also be propagated by layering of canes or by cuttings. Wild grapevines grow on their own roots unless cultivated by humans that may employ rootstock. Climbing vines grow naturally supported by trees and shrubs, and they tend to be resistant to many common vineyard diseases.

European Vitis Vinifera Grapes. These are domesticated cultivars and are self-fertile. They are usually propagated asexually via cuttings to maintain the character or the grapes and the wine made from them. These domesticated vines are often on rootstock developed to resist specific soil issues or modify the growth properties of the vines. Rather than grow wild, domesticated vines are pruned & supported by trellises and guide wires often to balance the amount of fruit and canopy, control sunlight on the fruit, optimize fruit production and make harvesting quicker and easier. Vinifera grapevines can be susceptible to many diseases and usually require application of fungicides and insecticides.

What are Texas’s Native Grape Varieties?

It is reported that there are as many as 13 native grape species and 100 named varieties of wild grapes in Texas. This is more than any other state, something that we have to thank for Texas’s many varied eco-regions and habitats. A good summary of native grape species in Texas is provided in the book, Grows in Texas, by Jim Kamas, a Texas A&M Agrilife viticultural specialist. This is the book I use as the primer in my Specialist of Texas Wine advanced class that will be next held in October (live via Zoom from The Texas Wine School). In this blog, I will focus only on a few that are considered important and related to wine production.

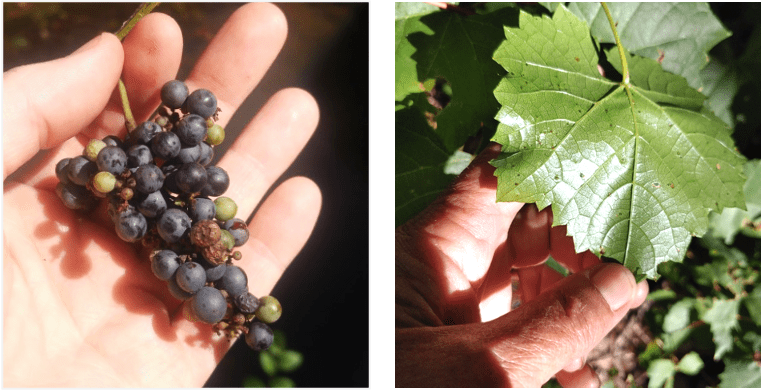

Vitis rotundafolia – The Muscadine Grape. This species is unique among grape species as it has 40 chromasones, whereas other Vitis grape varieties have only 38. It is generally found growing in east Texas (east of I-45) and eastward to the southern Atlantic states. The westerly extent of Muscadine reaches Harris County. This is a rural wine making grape in much of this region. It is often referred to as being “an acquired taste” offering “foxy or musty” aromas and, to some people, the odor of something like “rubber cement”. Muscadine likes moist, well-drained sites often under trees. Its grapes are large and black, green or brown, but with only a few grapes to a bunch that often ripen and drop individually. The leaves are cordate to ovate.

Vitis mustangensis – The Mustang Grape. The area of its growth covers much of central, north and east Texas growing along rivers, creeks and roadways. Mustang grapes are small and dark-skinned, and found in bunches from 3 to 12 grapes. Its cordate to ovate leaves start lobed, but the sinuses between the lobes fill-in during summer, and its lower surface is a powdery white. Mustang is a vigorous, high-climbing, long-running and hearty species; old vines have been found more than 50’ long and a foot in diameter. This is the grape recorded in history that was used to make wine by European Texas settlers in the 1800s. It was what they harvested to make wine after the European vinifera grapevine cuttings they brought with them died.

Vitis berlandieri – The Winter Grape. This grape species has a special ability to thrive in calcareous (high pH) soils in well-drained sites in central and west Texas and grows in limestone hills and creek bottoms. It has small bunches of dark-skin grapes (not very efficient for wine production) and its leaves can vary from cordate to ovate with narrow-to-broad sinuses. Mustang is an aggressive climber and ripens fruit in the Fall. However, it gained its name as the Winter Grape since the grapes can hang until a Winter freeze comes when the they become sweeter. This was on top of T.V. Munson’s list of grapes to use as rootstock in France in the late 1800s. More on this in the Part 2 blog.

Vitis arizonica – The Canyon Grape. Arizonica grows in ravines and gulches in higher altitudes in west Texas and the westward states. It has small light to dark-skin grapes in loose bunches. It has been observed to have either serrated or lobed cordate leaves. Arizonica vines tend to spawls and only weakly climbs. It has shown to be very disease resistant including a single gene cluster that conveys resistance to Pierce’s disease.

Vitis aestivalis – The Summer Grape. This grape covers a large area from Canada to Texas to Florida to Maine preferring drier upland habitat. Vitis aestivalis is a vigorous climbing vine growing into nearby shrubs and trees with grapes ripening from mid- to late-Summer. The leaves are usually a little broader than long with a variable cordate shape, from unlobed to deeply three- or five-lobed, green above, and hairy below. The moderate size grapes are found in bunches. It is the official grape of Missouri and its interspecies-hybrids include the wine-producing species of Norton and also genetic linkage to Texas favorites like Black Spanish and Blanc Du Bois.

Part 1 Takeaway Message

Texas’s Native Grapes are good for local wildlife and local and migrating birds offering shelter, insects for food, and sweet energy-laden grapes for moisture and a sweet energy drink. As indicated above, identifying Texas’s native grapes requires more than just looking at leaf shape. It requires a defining a combination of attributes that include leaf shape and undersurface, grape size and cluster type, and the habitat where it is found to grow.

— — — — —

In Part 2, the blog will explore memorable moments in history of Texas native grapes and their worldwide legacy. It will include their international role along with T.V. Munson, often referred to as “The Grape Man of Texas” in the 1800s, again afterwards, and reappearing again to aid modern-day Texas viticulture. Last but not least, we will also discuss how to propagate and grow Texas’s native grapes.

Click here to link to Part 2 – Texas Native Grapes: Know Them, Grow Them… Cherish Their Worldwide Legacy (Memorable Moments in History & Even Now).

Be the first to comment