STANDING AT THE CROSSROADS (Part II)

ADAPTIVE VARIETY SELECTION AND THE UNCERTAIN ROLE OF IMIDACLOPRIDS IN THE FUTURE OF SOUTHERN GRAPE CULTURE

By: R.L. Winters, Fairhaven Vineyards

Master Horticulturist/Ampelographer Fairhaven American Hybrid Research Foundation

[VT – Please welcome back VintageTexas guest blogger R.L. Winters in this three part blog on the impact of the use of imidacloprid pesticides our grape culture in Texas and the American Southland. Click here to read Part I – The MYSTERY. Click here to read Part III – WHAT YOU CAN DO.

NO WAY HOME

In the case of sublethal imidacloprid dosing, the pollinators aren’t killed directly, but absorb or transfer enough of the chemical to the brood to produce toxicity that overlaps into successive generations. In the process of unraveling this paradox, it has become clear that the neonicotinoid was being transferred back to the colony in the form of contaminated pollen. The pollen is then consumed and or conveyed to the developing larvae. As the larvae matured, the ingested tainted pollen delivers the sub-lethal dose that would manifest itself by damaging the foragers neurons to the degree that their ability to master the vital, million-year-old skills of colony behavior, was severely damaged.

As is detailed in the report published by Ecotoxicology 2012 May 21(4) 973-992; “Bees trained to forage on artificial feeders, Bortolotti et al. (2003) noticed that a 500 meter distance between the hive and the feeding area resulted in no foragers at the hive/feeding area up to 24 hours after treatment when foragers were fed with imidacloprid at 500 and 1,000 μg l−1. The latter authors also found that a lower concentration (100 μg l−1 imidacloprid) caused a delay in the returning time (to hive or feeding area) of the foragers”.

At the core of the mystery of the disappearance, the explanation seems to be a macabre set of symptoms that include the inability to navigate correctly.

The foragers use a complex system to find food and nectar sources and chart a return course to the colony. When these instinctive systems were damaged the foragers simply couldn’t find their way back to the colonies! The maximum life span of the foragers outside the colony is a mere three days so their fate was sealed, not just a few of them, but rather, by the millions.

Because of imidacloprid’s lightning ability to penetrate the plant cell structure, minute quantities of neonicotinoid were metabolized by the crop plants and that micro-dose was ultimately transferred to both the pollen and nectar from the flower structure. The mobility of the neonicotinoid to the pollen grains has been clearly demonstrated. Several studies have examined the translocation of imidacloprid from seed treatment to different parts of sunflower (Helianthus annuus) plants.

A scientific study (Schmuck et al. 2001) determined imidacloprid residues in pollen samples of maize and sunflower that received a seed treatment (Gaucho WS, 700 g kg−1). In 58% of the pollen samples, imidacloprid was found with an average concentration of 3 μg kg−1 (range 1–11 μg kg−1) for sunflower. In 80% of the maize pollen samples, imidacloprid was found at an average concentration of 2 μg kg. It was this minuscule dose that was at the root of the unforeseen effects that have ravaged hundreds of millions of pollinators on a global scale.

The mechanism of the neural damage to the foragers isn’t fully understood, but tests on both pollen and nectar samples have shown the presence of the neonicotinoid molecule, and the effects of sublethal dosing is well documented; the rest of the puzzle is coming into clear perspective.

In Europe where regulatory agencies tend to act on the side of caution, the removal of imidiacloprid from the market has ended the death spiral of Colony Collapse Disorder. Simply dismissing the effects that this product has on pollinators on a global scale is a path fraught with peril.

Fully 35% of all food crops, 15 billion dollars of production, including common fruits and vegetables, rely on the intervention of pollinators to complete the cycle of production. The prospect of produce, grains, and fruit products reaching astronomical prices due to scarcity, and then simply disappearing from the shelves isn’t a fiction. But rather a looming reality.

THE KNOWN FACTORS

The follow eight points are some of the currently documented facts regarding neonicotinoid use and are supported by numerous research papers:

- Neonicotinoid residues found in pollen and nectar are consumed by flower-visiting insects such as bees. Concentrations of residues can contain both lethal and sublethal dose levels.

- Neonicotinoids can persist in soil for months or years after a single application. Measurable amounts of residues were found in woody plants up to six years after application.

- Untreated plants may absorb chemical residues in the soil from the previous year.

- Products approved for home and garden use may be applied to ornamental and landscape plants, as well as turf, at significantly higher rates (potentially 32 times higher) than those approved for agricultural crops.

- Neonicotinoids applied to crops can contaminate adjacent weeds and wildflowers.

- Imidacloprid, clothianidin, dinotefuran, and thiamethoxam are highly toxic to honey bees.

- After plants absorb neonicotinoids, they slowly metabolize the compounds. Some of the resulting breakdown products are equally toxic or even more toxic to honey bees than the original compound. Some of the metabolites have higher toxicity to humans.

- Honey bees exposed to sublethal levels of neonicotinoids experience problems with flying and navigation, reduced taste sensitivity, and slower learning of new tasks, which all impact foraging ability.

PAIRING WITH IMIDACLOPRID

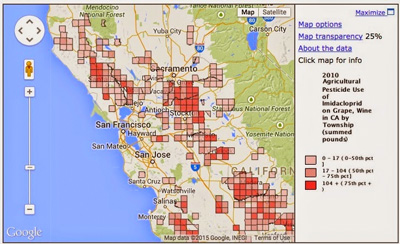

In 2009, some 34,000 pounds of imidacloprid were applied to 182,000 acres of wine grapes, about 36% of vineyards. Since this use data was collected and published in the 2010 Report On Pesticide Use By Commodity the total poundage and demographic of use has expanded exponentially.

As a grape grower, I have spent a great deal of time contemplating the potential of the systemic imidacloprid to affect the safety and integrity of the finished wine. During various seminars I’ve attended, I have posed the simple question, several times, to the learned speakers; “Does imidacloprid cross the developmental boundaries during the early stages of berry development and is it present at harvest?”

The majority of the responses were either evasive or dumbed-down answers that asserted that the product was “safe” and therefore the issue wasn’t something that the grower need be concerned with (It’s labeled for grapes so it’s okay!).

The answer to the question regarding its distribution in fruit becomes rather obvious when current testing reveals that not only is the product present in the plant body for extended periods of time, but imidacloprid is able to invade even the most remote tissues of vine anatomy, right down to the guttation of nectar and to the pollen bodies themselves!

Current testing conducted by SPEC CertiPrep and published in a report by Patricia Atkins, has revealed that the neonicotinoid molecule is present in 35% of samples tested in a far ranging demographic of finished wines at an alarming level of 3 ppm, and in certain samples as high as 35 ppm (using mechanical sample agitation). Current EPA food safely tolerances for residues of imidacloprid and its metabolites in food range from 0.02 ppm in eggs to 3.0 ppm in hops. (the discrepancy of this wide range of safety tolerance isn’t clear).

Safety tolerances for imidacloprids in finished wines are non-existent.

All of this raises some serious questions regarding the effects of imidacloprids in human metabolism. Most frightening of all is the lingering question regarding the testing of this complex, and aggressive agent, and it’s safety for human consumption. Even though it’s toxicity to insects is well researched the guanidine metabolite of imidacloprid is significantly toxic to humans and the knowledge base surrounding the health effects of this component of the molecule is nearly nonexistent.

Is the same faulty evaluation of “sub-lethal” dosing that has has seen the decimation of the pollinators operative when it comes to human consumption?

The omnipresence of this designer systemic has been the dirty little secret of wines produced throughout the “Pierce’s Belt” of the southern tier of states. It’s the ugly stepchild that the wine industry has kept carefully hidden in the back bedroom out of sight.

To be continued…

PART III – WHAT YOU CAN DO IN 10 STEPS